LEGENDS IN UROLOGY

The Canadian Journal of Urology™

August 2024

Jerry G. Blaivas, MD

Professor of Urology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Adjunct Professor of Urology, SUNY Downstate Medical School

New York, New York, USA

To say that I am humbled to be counted amongst the luminaries who have received the honor of being recognized as a legend in urology is an understatement. Then, I read the autobiographical pieces by Helen O’Connell, and Irwin Goldstein, some recently inaugurated Legends, both of whom I know pretty well. Then my humility turned

to unease and I read the bios of some more “Legends.”

I suggest that you do the same. Start with Professor Denis’ account of himself. Please read mine first, though, so I may enjoy my own moment in the spotlight. Then, go on and read about the other Legends in Urology; quite an interesting, remarkable and inspirational group. I begin by paraphrasing the guidelines for the author of Legends in Urology.

1) Describe what I am most proud of:

a. Adhering to my own ethical/moral/intellectual standards – an amalgamation derived from my parents

and mentors (personal and virtual).

b. Doing my best to pass those standards on to others.

2) Actually, I was supposed to describe those contributions that I am most proud of.

Here they are, but I must admit, only one of these was entirely my own idea.

a. Incorporating videourodynamics into clinical practice for all patients with lower urinary tract disorders.

b. Characterizing the physiology, neurophysiology, and pathophysiology of the lower urinary tract.

c. Describing the differential diagnosis of “BPH.”

d. Developing and improving surgical techniques for autologous rectus fascial slings, augmentation and reduction cystoplasties, urethral strictures in women, and vaginal mesh complications.

e. Developing classification systems for detrusor sphincter dyssynergia, stress incontinence in women, urinary urgency, overactive bladder, and nocturia.

f. Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Neurourology and Urodynamics.

g. Co-founder of Symptelligence Medical Informatics.

h. Developer of A New Paradigm for Healthcare Delivery.

3) Why and how I selected my professional paths?

I have no idea – mostly dealing with unexpected twists of fate.

4) Who were my most impactful mentors?

A mentor is “an experienced and trusted advisor.” Herein I describe three kinds of mentors – personal, professional and virtual.

Personal mentors – my parents (Marilyn nee Shenker and Murray Blaivas, wife (Sue nee Lieberman), three daughters (Heidi, Kim and Lindsey – yes, adult kids can be “experienced advisors”), and my high school track and football coach (Irving “Moon” Mondschein).

Professional mentors – The two most important were urologists Nageswara Rao Chadalawada and Carl Olsson. Alan Retik, Edward J. McGuire, Lenny Zinman, and many others are described below. Virtual ones are countless, from history, philosophy, poetry and, oh yes, urology. Of course, they are not actually mentors; they are more like role models, but I took what they said and did so personally that, to me, they were virtual mentors. Here they are, the most impactful of many virtual mentors – Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, William Wordsworth and Robert Frost, Aristotle, Plato and Immanuel Kant, and urologists Emil Tanagho and Richard Turner-Warwick and Gynecologist David Nichols.

5) What do I consider the key to my success?

Good luck, good luck, good luck, integrity, overriding intellectual curiosity, a natural affinity for writing and considerable prodding by Carl Olsson. Add to that, a little advice from Alan Wein, my good friend Jeffrey P. Weiss, and my daughter Kimberly, a lawyer by training. She was second in command of the Institute for Bladder and Prostate Research, Editorial Assistant of Neurourology and Urodynamics, and the forever editor of my written words (she may edit this out). They all teamed up with my wife, Sue, and daughters, Heidi and Lindsey to keep me from doing dumb things.

6) What lasting message do I want to leave for future generations of urologists (and other humans)?

Here is my advice (mostly paraphrased from great minds):

a. Find a job that you love, and you’ll never work a day in your life (Confucius).

b. Be prepared, do your homework, don’t bullshit. (Boy Scouts of America, Carl Olsson).

c. The opposite of “don’t bullshit” is “fake it until you make it.” If you fake it, hope to make it before they take it (away when you are caught). My advice? Don’t fake it.

d. Doing the right thing is a reward in itself (Murray Blaivas, my father).

a. A corollary to that from my good friend Emil ”Jack” Jachmann Is “Right is right even if no one is doing it and, Wrong is wrong even if everyone is doing it.” (First attributed to St Augustine).

e. Work your hardest and give it your all; I have 100% confidence in you (Irving “Moon” Mondschein – I think he said that to all of his athletes).

f. “Learn from the mistakes of others, you can’t make them all yourself.” (Eleanor Roosevelt) A corollary to that is learn to have the thickest of skins. Consider every single criticism or insult you get carefully and ask yourself, why did that person say that? If it’s warranted, correct it. You will become a better person. If not, be wary of that person in the future.

So, how did I get to be what I am – the old nurture versus nature argument? In my case, I think it’s a little of both and a lot of luck.

With pride, Louis Dennis wrote that he’s been described as a” free thinker;” I’ve been repeatedly described as someone who “thinks outside the box.” That’s not necessarily a compliment, but I do think it’s true.

I was the first in my family to go to college. My father and his father were high school graduates; my other grandfather made it through the 8th grade. Yet, without a formal education, these three men became very successful and were all granted patents. My paternal grandfather patented one of the first devices for administering blood

transfusions and co-authored the major textbook on clinical medical laboratory medicine with a famous pathologist. He founded a clinical medical laboratory called Kings County Research Laboratory.

Like many heroes of his generation, my father enlisted in the army and fought in WW2 while my mother was pregnant with me. He came home two years later. Many others of his generation never returned, so my good luck started there.

When my father got out of the army, he joined my grandfather; together, they grew their laboratory business. It became one of the largest clinical medical labs in the world and the first to be computerized. Along the way, my father got the idea for the vacutainer tube, which he sold to Becton-Dickinson. He also patented the methodology of putting a bacterial culture medium at the bottom of a test tube containing a swab to obtain the specimen – a method still in common use today. The lab was eventually sold to Hoffman La Roche, an international healthcare behemoth, and it became Roche Diagnostics. So, these three men served as both my nature and nurture.

My parents were very kind, caring, and generous people, as was my entire extended family, all of whom made me feel like I could do anything that I put my mind to. That’s the beginning of the nurturing part. I was born in Brooklyn, NY, and lived the first 3 years of my life with my mother, grandmother, and great grandfather in a one bedroom

apartment. Then, when my father came home from the war, we moved to a tiny little house with two bedrooms – my sister and I shared the second bedroom. We moved 4 more times before I got to high school and twice more in high school, but thankfully, I spent four straight years in one town and graduated from Lawrence High School in Long Island, NY.

In high school, I focused on sports (football and track). Enter my first and most impactful mentor – Irving “Moon” Mondschein,” my high school track and football coach. He was a charismatic, inspirational person with the wisdom of Solomon, who did everything in his power to ensure everyone on his teams gave their all and rose to

the heights of their potential.

I went on to Tufts University, where I captained the track team and played varsity football until my sophomore year when I rammed my head into a big guy’s belly, whom I was supposed to block. It was like hitting a brick wall; I actually saw stars, fell to the ground, and when I lifted my head, I saw this huge creature who looked about ten

feet tall and maybe 300 pounds. At 5’10” (rounded up) and weighing 155 lbs, my football career ended.

My high school and college academic careers were relatively undistinguished, but in college, I received a superb education and learned critical thinking along the way. I barely got into medical school, but then, somehow, at end of my second year, I scored in the top 1% of the country on the National Medical Board exam.

Oh, one more thing I got out of college, my wife of 59 years, Sue. We married after my second year of medical school, and she and my three daughters remain my very best friends to this day. Sue, a psychiatric social worker, trained with a pioneering behavioral therapist, and she herself pioneered behavior therapy for LUTS and developed

many of the techniques that we still use today.

I graduated from the Tufts University School of Medicine in 1968 and began a general surgical residency at Boston City Hospital, intending to be a general surgeon. Every other night and weekend, I was on call and moonlighting lone weekend a month to make ends meet. That meant that I had one weekend off a month. Five years of general

surgery was cut short after 2, when I and our entire residency class were drafted to serve in the Vietnam conflict. I served two years as an orthopedic surgeon (go figure), presented my first-ever paper at a national meeting, and developed a profound respect for our military.

Enter my next most impactful mentor, Nageswara Rao Chadalawada. Nag was an Assistant Professor of Urology at The Tufts New England Medical Center, where I did my urology residency. As if I was not thinking enough already, Nag made me think and question everything that I knew. Every day, he asked me a question that I could not answer, and before the sun set the next day, I always had an answer for him. He and his wife, Suddha, an ophthalmologist, were the kindest people I ever met who never deviated from their single-mindedness purpose – to serve humanity. After training in the US, Nag and Suddha returned to India, where they founded a medical, dental, and nursing school and a charity that “adopted” 400 adjacent villages and provided free healthcare for their impoverished neighbors. Nag also became President of the Indian Urologic Society.

At Tufts, two gifted urologic surgeons – Bob Spellman and Alan Retik, taught me how to operate. The principles they espoused have served me well over the 4 decades since I first learned them (whether it’s robotics or open surgery) – obtain adequate exposure, handle the tissue gently, dissect with traction and counter traction, and, for

anastomoses, insure an adequate blood supply and tension free approximation of the tissue.

During those years, under the tutelage of urologists Carl Olsson, Alan Retik, Nageswara Rao, and Bob Krane and physiatrists Kamal Labib and Allain Rossier, and in collaboration with my co-residents Stu Bauer and Mike Siroky, my passion for neurogenic bladder and the application of urodynamics to voiding dysfunction in men, women and children was born. We developed and opened one of the first video-urodynamics units in the world and did video-urodynamic studies 5 days a week.

Kamal Labib was a gifted electrophysiologist who taught me the nuances of electromyography of the pelvic floor. Allain Rossier was a preeminent world authority on spinal cord injury and neurogenic bladder. His mentorship was invaluable, igniting my lifelong passion for spinal cord injury. We staffed a weekly clinic for neurogenic

patients that evolved into one of the first multi-specialty clinics for patients with neurogenic bladder. Our detailed neuro-urologic evaluations provided us with a treasure trove of material for clinical research that probed into the physiology, pathophysiology, and neurophysiology of micturition. Over the ensuing eight years, we published over thirty papers on these topics.

A large surgical experience dominated my first five years in practice at Tufts – I operated 4 days a week, mostly nephrectomy, cystectomy, open stone surgeries, and TURPs. I also spent a week with F. Brantley Scott in Houston and was already doing sphincter and penile prostheses by 1977.

In 1981, I moved to the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York and was appointed Director of the Neurourology Division, Vice-Chairman of the Department, and eventually Professor of Urology. I stopped at Yale on the trip from Tufts to Columbia and spent a few days with Ed McGuire, who became a lifelong friend and mentor. Ed was a most remarkable person – a brilliant, intuitive thinker who seemed to innately understand the physiology and pathophysiology of the lower urinary tract based on his own clinical and urodynamic observations. He was a singular giant in our field, a kind man of impeccable character and a genuine war hero. He was awarded the Bronze Star and will be entombed in Arlington National Cemetery. Though he spoke but one language, Ed could tell a joke with every dialectical accent known to man – one of the funniest people I had ever met.

On that visit, Ed taught me how to do an autologous fascial pubovaginal sling. I think that it was me who modified the technique of pubovaginal sling by using the rectus fascia as a graft rather than a flap. No matter, that modification allowed us to place the sling with no tension at all. In 1998, we published a landmark paper on the use

of autologous fascial slings for women with primary stress incontinence (Chaikin et al. Pubovaginal fascial sling for all types of stress urinary incontinence: Long-term analysis. J Urol. 1998. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)62524-2). Prior to that, slings were reserved for only those who had failed multiple prior procedures. I believe that set the

stage for the developing mid-urethral synthetic slings, which, in my opinion, is a double-edged sword – comparable efficacy, shorter OR time, but with too many refractory life style-altering complications compared to autologous slings (Blaivas et al. (2015). Safety considerations for synthetic sling surgery. Nature Reviews. Urology 12(9):

481-509. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2015.183).

Once at Columbia, the focus of my clinical practice changed to the lower urinary tract, predominantly benign prostate problems, urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, neurogenic bladder, and pelvic organ prolapse; I no longer did urologic oncology except for bladder cancer, which I continue to this day. Over the following decades, I continued to see patients with ordinary lower urinary tract problems, but over time I developed a reputation for seeing complex voiding dysfunction such as failed surgery for BPH, refractory overactive and neurogenic bladder, as well as reconstructive urology, including complications from pelvic radiotherapy and prostate cancer surgery,

urethral diverticulum, vesicovaginal fistula, urethral strictures, and vaginal mesh complications.

With my job at Columbia came mentor number three, Carl Olsson, Chairman of Urology at the College of Physicians and Surgeons. Carl is a brilliant man endowed with great personal fortitude and character. He is a superb educator, and he once told me something I will never forgot – the best way to learn is to teach. As I grew older, I substituted “write” for “teach” because when you write, it is forever (unless they burn your book).

In 1981, Carl inspired me to found the Journal Neurourology and Urodynamics, which became the most important peer reviewed journal for lower urinary tract disorders. It was Carl who coined the term “neurourology.” I was Editor-in-Chief for about 25 years and authored an editorial for every issue, often on controversial topics which

sparked much debate. Carl supported me with sage advice about urology, business, and politics until his recent retirement.

At Columbia, I continued a significant effort in clinical research in clinical aspects and the pathophysiology of lower urinary tract disorders, focusing on urinary incontinence, “BPH,” and neurogenic bladder. I also collaborated with Robert Levin at the University of Pennsylvania and two AFUD fellows working under my direction, Mike Chancellor and Steven Kaplan, using an isolated rabbit bladder model to explore parameters of detrusor contractility. In 1988, I published an article describing the differential diagnosis of “BPH,” based mainly on the observations of Richard

Turner-Warwick (Blaivas JG. Pathophysiology and Differential Diagnosis of Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy. Urology 32:supp5-11,1988). Up until that time, “BPH” and prostatic obstruction were considered to be synonymous, and many men underwent and failed needless prostatic surgeries.

In 1992, I joined the voluntary faculty of what is now Weill-Cornell Medical School. Shortly after that began a collaboration with Jeffery P. Weiss, who is currently Chairman of Urology at SUNY-Downstate College of Medicine, the preeminent authority on nocturia and a remarkable human being. Our primary focus is in nocturia, phenotyping

lower urinary tract disorders, developing clinical pathways, and outcomes research in lower urinary tract disorders.

In 1998 I founded the Institute for Bladder and Prostate Research. This small not-for-profit sponsors and engages in research concerning the safety and efficacy of different treatment options for men and women with lower urinary tract disorders and most recently, the development of a New Paradigm for Healthcare Delivery.

In 2013, I co-founded Symptelligence Medical Informatics, LLC, a software company that designs clinical decisionmaking and outcomes research software. This software provides the infrastructure for all of our outcomes research, phenotyping, and clinical pathway development.

In 2017, I joined the faculty of The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai under Chairman Ashok Tewari, who has built one of the finest urologic oncology programs in the world. He is a superb surgeon/scientist and a charismatic leader. I’m honored to work there and continue my journey as a surgeon and clinical research scientist, pursuing

my passion to create a New Paradigm in Healthcare Delivery (Li et al, A New Paradigm for Outpatient Diagnosis and Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Utilizing a Mobile App/Softward Platform and Remote and In-Office Visits: A Feasibility Study. Urology Practice. 2021 January;8(1):11-17).

It’s an age-old adage that we all stand on the shoulders of those who came before. I stand on many shoulders, listed above, and many more who are active in the recesses of my brain. I want to thank you all. I don’t distinguish between the living and those who’ve passed on because I believe in the soul, and I hope that some of you are listening.

Jerry G. Blaivas, MD

Professor of Urology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Adjunct Professor of Urology, SUNY Downstate Medical School

New York, New York, USA

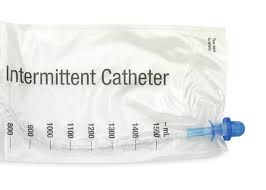

At the UroCenter of New York, it’s not uncommon to hear from our patients that they’re afraid to try SIC, or that it’s absolutely not for them. Some of the questions we hear are: “Is it going to hurt?” “How will I know when it’s in far enough?” “Don’t I need to use sterile gloves?” Sterile technique has been proven to be unnecessary for the vast majority of patients, although some doctors and patients prefer it. Though SIC is not a guarantee against infection, the risk is far lower than an indwelling catheter or living with a residual urine. All that is required is that you wash your hands before and after the procedure and clean the penis or the labia around the entrance to the urethra.

At the UroCenter of New York, it’s not uncommon to hear from our patients that they’re afraid to try SIC, or that it’s absolutely not for them. Some of the questions we hear are: “Is it going to hurt?” “How will I know when it’s in far enough?” “Don’t I need to use sterile gloves?” Sterile technique has been proven to be unnecessary for the vast majority of patients, although some doctors and patients prefer it. Though SIC is not a guarantee against infection, the risk is far lower than an indwelling catheter or living with a residual urine. All that is required is that you wash your hands before and after the procedure and clean the penis or the labia around the entrance to the urethra. Urologic Problems in Men

Urologic Problems in Men Urologic Problems in Women

Urologic Problems in Women