Rajveer S. Purohit, MD, MPH

First consider your medical history. If you’ve had any trauma to the pelvis, sexually transmitted infections, had anything inserted in the urethra – particularly if it was traumatic – you are at risk for having a stricture. Also, if you’ve had a stricture in the past and have developed urinary symptoms you are at much higher risk of a stricture. These are just a few of many things in your medical history that raise the possibility of a stricture.

First consider your medical history. If you’ve had any trauma to the pelvis, sexually transmitted infections, had anything inserted in the urethra – particularly if it was traumatic – you are at risk for having a stricture. Also, if you’ve had a stricture in the past and have developed urinary symptoms you are at much higher risk of a stricture. These are just a few of many things in your medical history that raise the possibility of a stricture.

But the past history can be misleading – about 1/3rd of the time, patients can present with dense strictures that have no known cause (called idiopathic strictures).

One additional indication of a stricture is if you currently have bothersome urinary symptoms. These include obstructive urinary symptoms including a slow urinary stream, urinary hesitancy, and a sense of incomplete emptying after you urinate – which is a sensation that after you urinate you still feel that you retain urine in the bladder.

Some patients can also present with what are termed irritative urinary symptoms which include urinary urgency, frequency, night time urination and even incontinence.

What makes reliance on symptoms difficult is that many of urethral stricture symptoms also overlap with other common urinary problems such as benign prostatic obstruction (BPO) and overactive bladder. Furthermore, on physical exam you might have an enlarged prostate but the primary source of your symptoms is actually a urethral stricture.

A little confusing, huh?

So what kinds of tests can be done to determine more definitively if you do have a stricture?

Common noninvasive tests we perform are the uroflow and post-void residual. We ask patients to urinate with a full bladder into a machine that measures, over time, changes in the speed of their urination and the amount that was urinated. After urination, we measure the amount of urine your bladder is still holding (residual urine) using a hand-held portable ultrasound. Patients who have strictures will not only often have a slow urinary flow measured by the machine but also a characteristic change (flattening) in the graph that measures speed over time. Again, however, many of these uroflow findings are mimicked by benign prostatic obstruction (BPO) as well.

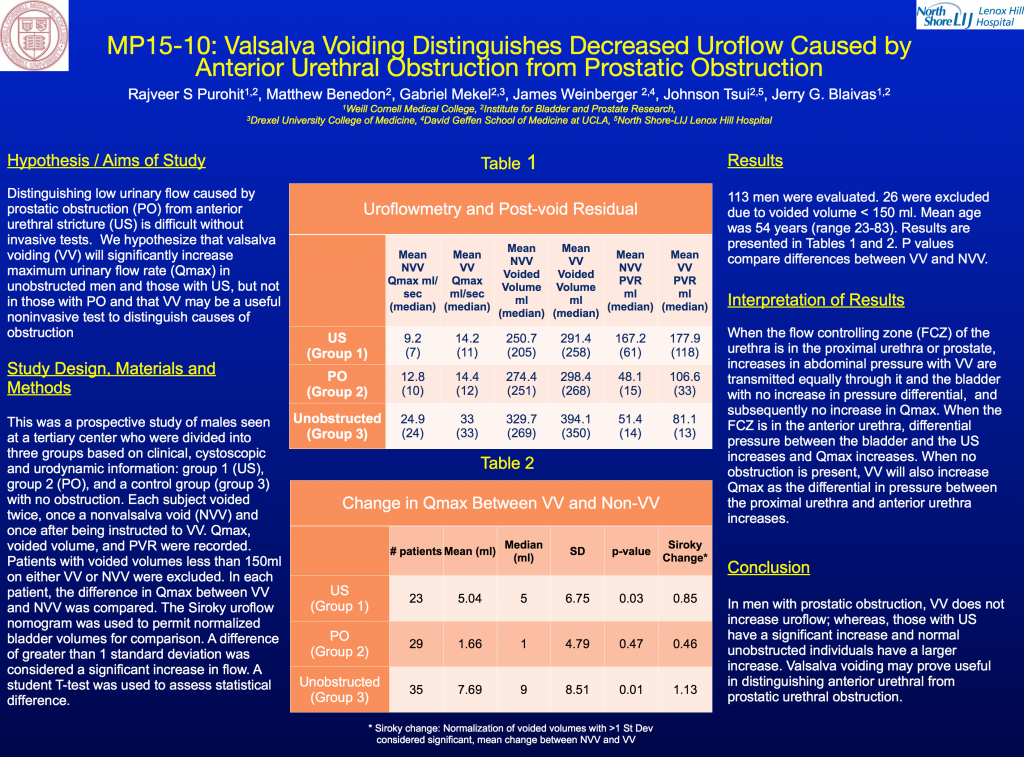

In considering this problem we’ve researched if minor tweaks in the noninvasive uroflow can help distinguish urethral strictures from BPO and presented our findings at the American Urological Association’s annual meeting in New Orleans in May 2015. We found that asking patients to increase their abdominal pressure while they urinated (termed Valsalva voiding) helped distinguish strictures from BPO. In patients with strictures alone Valsalva voiding will increase the speed of their urination while those with BPO will not. We think that this test will be particularly useful for those who may have had their strictures treated but are at risk for recurrence. Results from the presentation can be seen in the slide below.

The gold standard, however, for diagnosing the urethral stricture is more invasive x-ray studies called the Retrograde urethrogram (RUG) and sometimes voiding cystourethrogam (VCUG) and a study using a fiberoptic scope inserted into the urethra (with local anesthesia, of course!), called the cystoscopy.

We’ll talk in more about these tests on an upcoming blog post. Stay tuned!