Jerry G. Blaivas, MD, FACS Dr. Blaivas is a world-renowned urological expert, surgeon, distinguished author, educator, and medical pioneer. He was one of the founders of urodynamics and established many of the current surgical procedures used to correct stress incontinence, urinary fistulas, urethral diverticulum, overactive bladder and neurogenic bladder. He is also one of the… Continue Reading

See Our Main Site www.UroCenterofNewYork.com Blog Posts are Below: Continue Reading

What Are Calculi? Urinary Tract Stones

Have you been told you have calculi? These are more commonly known as urinary tract stones. And, they are not uncommon. Many men and women develop them over time. They are formed within the body’s urinary tract. Generally, they occur when urine is supersaturated with minerals including salt, uric acid, cysteine, and calcium oxalate, or others. In some cases, urinary tract stones can become quite large and, as a result of their size, can be painful to pass through normal urination. This can cause a great deal of pain and lead to worrisome health concerns if left untreated.

What Causes Urinary Tract Stones?

Doctors are not always sure what the underlying cause of this condition is. However, some research indicates that they may be due to the formation of a stone as a result of nanobacteria present. These nanobacteria form a calcium phosphate shell. The formation of Randall’s plaques is also associated with the development of urinary tract stones. When they do occur, the goal is less about learning why they are happening and more about learning what can be done about them.

Are You At Risk?

You may be at a higher risk of developing these if:

- You have a family history of developing them

- You have a relative dehydration level

- You are hyper parathyroid

- You have gout

- You have hypertension

- You suffer from metabolic disorders

- You take diuretics, calcium supplements, Vitamin D supplements, or other types of medications

- What Can Be Done About Urinary Tract Stones?

If you have these, your doctor will likely discuss several treatment options with you. The use of NSAIDs for pain can be used as a first line of treatment. In some cases, rehydration is necessary. In many cases, stones will pass spontaneously within one to three weeks. In some situations, when the stones are very large or very painful, surgery may be necessary. However, this is much less common than simply using medications to break up stones and to allow them to pass.

If you believe you have developed urinary track stones or you are at a high risk for doing so, talking to your doctor about it is the first step. The sooner you seek out treatment, the more likely that treatment is to work and the less your pain will be. Meet with one of the best urologists in the New York City area to learn more about your conditions and treatment options.

Call us at 646-205-3039 to schedule a consultation.

Tests to Diagnose and Evaluate of Urethral Strictures: Part 2

An additional test that we find to be very useful to evaluate a stricture is the cystoscopy. This cystoscopy is done in the office and is typically done one the same day as the retrograde urethrogram. After local anesthesia (usually lidocaine jelly) has been placed into the urethra a cystoscope is gently placed into the urethra. The cystoscopy allow direct visualization of the urethra as well as any other anatomic anomalies that may be present in the urethra. In addition, the cystoscopy may also reveal urethral lesions that are not well visualized on a retrograde urethrogram. The downside of the cystoscopy is that often a cystoscope will be too wide to permit passage through the narrow opening of the urethral stricture and, consequently, it can be difficult to estimate the length of the urethral stricture as well as the presence of additional strictures behind the impassable one. For this reason, we feel that a cystoscopy generally should be done in conjunction with the retrograde urethrogram to diagnose and evaluate urethral strictures.

The cystoscopy is useful to evaluate urethral strictures in other ways also. Dr. Purohit and Blaivas have developed and published a staging system for urethral strictures that relies on the use of cystoscopy. It is currently the only validated staging system available for describing urethral strictures. Typically, urethral strictures have been studied using a binary scale (or 2 part) in the medical literature – that is patients are reported as either having a stricture or not. We have found that the simple binary classification of strictures and analysis that are based on the simple binary staging system of strictures is often inadequate to fully describe the range of urethral strictures that patients can develop. Some strictures are very slight narrowing in the urethra that causes no symptoms and may never become a problem for patients. Other urethral strictures, however, are very tight and cause terrible suffering for patients. Our staging system is the first step to better incorporate the large variety of strictures. In our opinion not all strictures should be treated the same – in fact some strictures may not need any surgery at all!

Dr. Purohit and Dr. Blaivas’ approach incorporates the staging system and allows a more nuanced and individualized surgery. The Purohit-Blaivas urethral stricture staging system uses a 4-point system to describe the range of strictures that patients can have; it is based on cystoscopic findings alone. By having a four tiered system, we are able to better describe and study the range of strictures that the patients present with.

The staging system is as shown below.

We will discuss some of the research that has utilized our staging system in a future blog post.

Testimonial

Urocenter Tom & Florence

Tests to Evaluate and Diagnose Urethral Strictures: Part 1

Two of the most important tests to diagnose and evaluate a urethral stricture are the retrograde urethrogram (RUG) and a cystoscopy. The retrograde urethrogram can be done by a radiologist or by a urologist. In our experience the information gained when an urologist does the RUG is usually more helpful then when done by a radiologist, but many urologist may not do the RUG because they lack the x-ray facilities for the test in their office. In our office, we are able to do fluoroscopy and, consequently, retrograde urethrograms in the office to diagnose and evaluate urethral strictures. The RUG is typically done by placing the patient on his side with a bottom leg bent and the top leg straight. The penis is put on mild stretch and contrast is gently injected into the urethra using either a small catheter or a specially designed syringe. As dye is injected into the urethra, multiple x-ray images are take to look for narrowing suggestive of a stricture.

Urologists specializing in urethral reconstruction know what to look for and can shift the position of the patient during the study to maximize important information to plan the best surgery to correct the urethral stricture. When a radiologist does this test, however, they may not be aware of the diagnostic needs of the surgeon. It is not uncommon for us to need to repeat the retrograde urethrogram for a patient who has been diagnosed with urethral strictures because of the poor quality of the original films done by a radiologist.

The retrograde urethrogram provides critical information about the length and location of the stricture as well as the extent of spongiofibrosis (a term we’ve previously discussed) and the density of the stricture. The extent of spongiofibrosis has a great impact on counseling patients as to the best type of surgery to correct the stricture.

Occasionally, however, the patient may have multiple dense strictures or may have a stricture in the back (posterior) portion of the urethra which are not very well visualized by retrograde urethrogram. In patients with more than one stricture (termed synchronous urethral stricture) the dye may not get past the first stricture and the extent of the patient’s stricture disease can be significantly underestimated. In these cases, a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) in addition to the retrograde urethrogram can be a useful test to evaluate the patient’s stricture, particularly if surgery is anticipated for the patient. The voiding cystourethrogram is done by placing a suprapubic tube, or a catheter that enters the abdomen below the belly button and goes straight into the bladder. Dye is placed through the catheter directly into the bladder and the patient is asked to urinate while x-rays are obtained. The voiding cystourethrogram can help visualize the proximal portion of the urethra when the retrograde urethrogram alone is inadequate.

Rarely, we have found that an ultrasound done of the urethra may also be helpful. This was particularly helpful if we are concerned that the patient has more extensive spongiofibrosis than may be apparent on the retrograde urethrogram. We typically will do the ultrasound of the urethra prior to surgery to better anticipate the type of surgery the patient will need. In our next urethral stricture blog post we’ll discuss the usefulness of a cystoscopy for diagnosing urethral strictures.

Testimonial

Urocenter Clare Testimonial

Testimonials

Urocenter Rudolph Testimonial

Why you might think you have a urethral stricture

Rajveer S. Purohit, MD, MPH

First consider your medical history. If you’ve had any trauma to the pelvis, sexually transmitted infections, had anything inserted in the urethra – particularly if it was traumatic – you are at risk for having a stricture. Also, if you’ve had a stricture in the past and have developed urinary symptoms you are at much higher risk of a stricture. These are just a few of many things in your medical history that raise the possibility of a stricture.

First consider your medical history. If you’ve had any trauma to the pelvis, sexually transmitted infections, had anything inserted in the urethra – particularly if it was traumatic – you are at risk for having a stricture. Also, if you’ve had a stricture in the past and have developed urinary symptoms you are at much higher risk of a stricture. These are just a few of many things in your medical history that raise the possibility of a stricture.

But the past history can be misleading – about 1/3rd of the time, patients can present with dense strictures that have no known cause (called idiopathic strictures).

One additional indication of a stricture is if you currently have bothersome urinary symptoms. These include obstructive urinary symptoms including a slow urinary stream, urinary hesitancy, and a sense of incomplete emptying after you urinate – which is a sensation that after you urinate you still feel that you retain urine in the bladder.

Some patients can also present with what are termed irritative urinary symptoms which include urinary urgency, frequency, night time urination and even incontinence.

What makes reliance on symptoms difficult is that many of urethral stricture symptoms also overlap with other common urinary problems such as benign prostatic obstruction (BPO) and overactive bladder. Furthermore, on physical exam you might have an enlarged prostate but the primary source of your symptoms is actually a urethral stricture.

A little confusing, huh?

So what kinds of tests can be done to determine more definitively if you do have a stricture?

Common noninvasive tests we perform are the uroflow and post-void residual. We ask patients to urinate with a full bladder into a machine that measures, over time, changes in the speed of their urination and the amount that was urinated. After urination, we measure the amount of urine your bladder is still holding (residual urine) using a hand-held portable ultrasound. Patients who have strictures will not only often have a slow urinary flow measured by the machine but also a characteristic change (flattening) in the graph that measures speed over time. Again, however, many of these uroflow findings are mimicked by benign prostatic obstruction (BPO) as well.

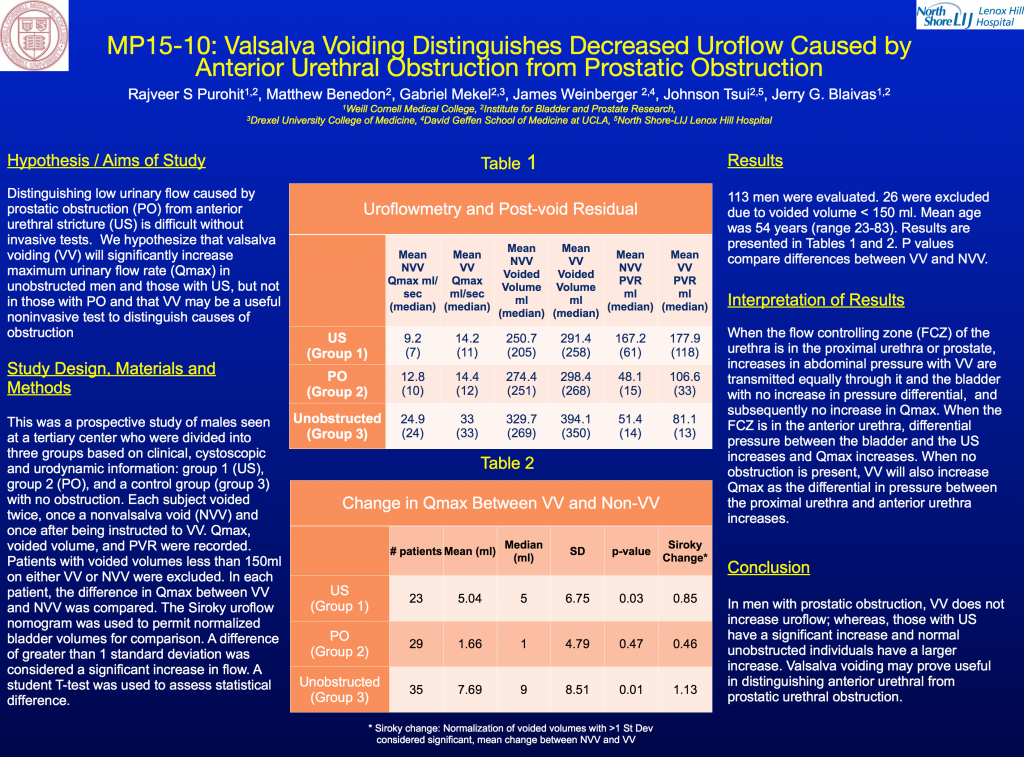

In considering this problem we’ve researched if minor tweaks in the noninvasive uroflow can help distinguish urethral strictures from BPO and presented our findings at the American Urological Association’s annual meeting in New Orleans in May 2015. We found that asking patients to increase their abdominal pressure while they urinated (termed Valsalva voiding) helped distinguish strictures from BPO. In patients with strictures alone Valsalva voiding will increase the speed of their urination while those with BPO will not. We think that this test will be particularly useful for those who may have had their strictures treated but are at risk for recurrence. Results from the presentation can be seen in the slide below.

The gold standard, however, for diagnosing the urethral stricture is more invasive x-ray studies called the Retrograde urethrogram (RUG) and sometimes voiding cystourethrogam (VCUG) and a study using a fiberoptic scope inserted into the urethra (with local anesthesia, of course!), called the cystoscopy.

We’ll talk in more about these tests on an upcoming blog post. Stay tuned!

Testimonials

Urocenter Theron Testimonial

Treatment of Stress Urinary Incontinence in Women: Mesh Sling or Natural Tissue (autologous) Sling

Jerry G. Blaivas, MD

Stress urinary incontinence in women is common and increases with advancing age. It is characterized by leakage of urine during coughing, sneezing, laughing, and all kinds of physical activity like running, jumping, lifting, etc. Most of the time stress incontinence is due to a weak sphincter (sphincteric incontinence), but sometimes the physical activity kind of jostles the bladder and causes it to contract by itself. The result is that the patient actually urinates without control. This is called stress induced detrusor overactivity also known as stress hyperreflexia. It is very important to make the distinction between sphincteric incontinence and stress hyperreflexia because the treatments are very different. Sphincteric incontinence is best treated with surgery; stress hyperreflexia is usually treated non-surgically.

The most common surgical treatments for sphincteric incontinence are slings. The efficacy of slings has been well documented by many research studies. The success rate is very high – over 85% of patients are pleased with the results (1,2).

There are two main kinds of slings – synthetic mesh slings, made of knitted plastic like threads and autologous fascial slings made of your own natural tissue called fascia, which is the strong white tissue that lines the muscles in your body. The success rate is nearly identical between the two types of slings, but complications can be much more troublesome and severe after mesh slings.

Pros and cons:

Mesh slings are much easier for the surgeon to perform. Surgery usually takes well under one hour and the patient is usually able to leave the hospital the same day or the next morning without a catheter. There is only a small incision, the recovery is much faster and patients can get back to normal activities sooner. Because of these apparent advantages, about 90% of slings performed in the United States are done with mesh. But there is a catch – nearly 10% of patients undergoing mesh slings sustain serious, life style altering complications and in another 5% the surgery was unsuccessful so the patient is still incontinent (3, 4).

Autologous fascial slings require a much higher degree of surgical training. Few surgeons are trained to do them well. The surgery takes about two hours and there is a 3 to 4 inch incision made in the lower abdomen. Most patients need to remain in the hospital for a day or two. The overall complication rate is about the same as with mesh slings, but serious, lifestyle altering complications are exceedingly rare.

We believe that the complication rate of synthetic mesh slings is under-reported in the peer-review literature and underappreciated by most surgeons and that is why they have achieved such popularity. In 2014, we conducted a systematic review of the medical literature to assess serious complications caused by mesh slings. These complications included those that necessitated more surgery such as a urinary blockage (urethral obstruction), erosion of the mesh into the vagina, bladder, and urethra, urinary fistulas, and blood vessel and bowel injury and serious infections. Other serious complications included those that were unresponsive to treatment and were lifestyle altering such as chronic pain, loss of bladder control (de novo overactive bladder). These serious complications were seen in about 10% of patients and in another 5% to 10% the original incontinence was unchanged or even worse.

The overall quality of the studies included in the review was judged to be poor with respect to complications. A particular shortcoming was the fact that the vast majority of the studies only followed the patient’s for six months to two years after the mesh sling operation, yet these serious complications occurred as long as long as 10 or more years after the original mesh sling surgery.

Concluding remarks -These complications are not inconsequential and they could happen to you! If you are considering sling surgery, be sure to do your homework. It is not enough for your doctor to tell patients that sling surgery is safe and effective. A 90% chance of not developing a lifelong problem with pain might seem pretty good, but when you realize that this is one out of 10 patients, the odds might not seem so great after all – especially if it happens to you.

Do the benefits of mesh sling surgery outweigh the risks? Does a fast outpatient procedure with a tiny incision and a quick recovery outweigh a 10% bad outcome? That’s for you to decide, but you need to be armed with accurate information. So ask your surgeon about her training. How experienced she is with both mesh slings and autologous slings? How long has she been doing these kinds of surgeries? Be sure to seek opinions from surgeons who are experienced with both kinds of slings. What does she think about what you have read here?

Then decide for yourself!

1. Dmochowski RR, Blaivas JM, Gormley EA, Juma S, Karram MM, Lightner DJ, Luber KM, Rovner ES, Staskin DR, Winters JC, Appell RA. (2010). Female Stress Urinary Incontinence Update Panel of the American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc, Whetter LE. Update of AUA guideline on the surgical management of female stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. May; 183(5):1906-14. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.02.2369. Epub 2010 Mar 29.

2. Blaivas, J. G., & Chaikin, D. C. (2011). Pubovaginal fascial sling for the treatment of all types of stress urinary incontinence: surgical technique and long-term outcome. Urol Clin North Am, 38(1), 7-15, v. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2010.12.002.

3. Blaivas, J. G., Purohit, R., Benedon, M., Mekel , Stern, Billah, Olugbade, Bendavid , Iakovlev. Safety considerations for synthetic sling surgery. (2015). Nat Rev Urol. 2015 Sep;12(9):481-509. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2015.183. Epub 2015 Aug 18.

4. Dunn, G.E. et al. Changed women: the long-term impact of vaginal mesh complications. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 20, 131-6 (2014).

Testimonials

Urethroplasty Experience for Urethral strictures with Dr. Rajveer Purohit

Urologic Problems in Men BPH and other urinary issues Incontinence Kidney Stones Sexuality & Hormones Prostatitis Prostate cancer treatment complications Urethral stricture Urological cancers Continue Reading

Urologic Problems in Women Incontinence Mesh Complications Vesico-vaginal fistula Prolapse (dropped bladder) Nocturia Urological cancers Urinary infections Kidney stones Neurogenic bladder Continue Reading